Examining the interaction between brand, product, and the customer journey.

Brand Strategy Definition and Customer Journey Mapping are the chocolate and peanut butter of Experience Design: delightful on their own, absolutely magical when combined skillfully. And sometimes very messy to work with.

Branding Strategy models often use structural metaphors like foundations, pillars, pyramids, and houses of various description. The point is to encourage a sense of stability and consistency over time, the rationale being that while products may come and go, brand perceptions are built over many years, or even decades.

Pillars are strong and stable; build them once, and you're set for a long time...

In contrast, it’s a chronological approach that frames Customer Journey Mapping. It’s usually depicted as a timeline, in which a potential customer needs to be guided across key touchpoints of interaction with a product or service. It’s an excellent format for thinking beyond the moment the sale is made, extending the frame of reference before and after that transaction to what causes it, and how the usage experience can lead to another purchase.

...sometimes too long. When the world changes around you, stability can be a liability.

The simplicity of both Branding Strategy and Customer Journey Mapping work well for those purposes, but like any simplification, they often leave out some potentially important details. Simplifications are based on assumptions. Brand Strategy structures assume that their precepts need to be absolute and static; Customer Journey Mapping assumes that the journey itself will progress the way that product category always has in the past.

Yet products and the categories in which they are presented are fluid and complicated. By questioning the assumptions behind the tools we’re using, we can identify opportunities others might have missed. This is more difficult than it sounds. Brilliant innovations and knuckle-headed blunders are hard to tell apart in their larval stage. Distinguishing between the two requires exploring the fuzzy areas in between useful simplifications and lazy assumptions.

Experience Design represents a more holistic approach to navigating that territory, one that’s better suited to the complexity of the real world than using either Branding Strategy or Customer Journey Mapping separately.

As an example, we can examine the Entertainment industry, a category we all use and one that never stops changing.

The plural in “going to the movies” comes from the very different way the movie-going “journey” was structured up until about 1960. Feature films were not shown using today’s specific schedules; there was a looping program (cartoon/newsreel/serial/B-movie/trailers, and then, finally, the feature film) that ran continuously throughout the day. You entered that loop at whatever point you happened to show up, and once you saw the same scene as when you entered, you knew you had seen all there was to see. That’s the origin of the phrase “This is where I came in.”

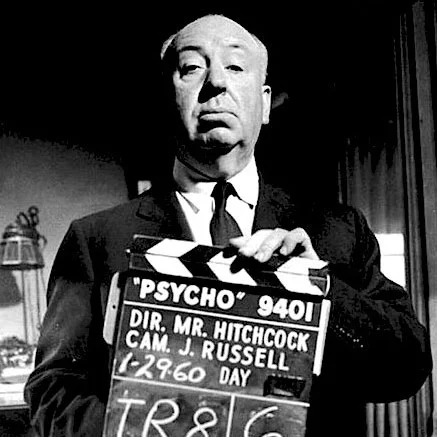

So what happened in 1960? Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, that’s what. Psycho wasn’t just a fantastically scary movie, it messed with the movie-watching customer journey in a way that made seeing the movie an even better experience.

Hitchcock realized the existing movie theater loop format presented a problem for Psycho. Unlike most suspense or horror films before it, it did not rely on cheesy space aliens or monster costumes for its impact. It generated suspense through realism, which is actually more unsettling than fantasy. It did away with traditional movie pacing too, doing completely unexpected things like killing off what appeared to be the main character (played by the movie’s biggest star, Janet Leigh) only 35 minutes into the story. Throw in its chilling ending, and you have a truly ground-breaking masterpiece.

Breaking all these rules within the movie itself was a very effective way of manipulating an audience, but useless if people happened to show up 50 minutes into the movie. At the very least, those people who came specifically to see Janet Leigh would be wondering why she wasn’t in the flick.

Hitchcock knew he needed to rethink, and control, the typical movie-watching journey if the movie itself was going to be experienced in the most effective way.

Hitchcock’s solution was the famous “No one will be admitted to the theater after the start of the performance” marketing campaign, in which puzzled theater managers were told to refuse entry to paying customers if their timing happened to be wrong. So much for the customer always being right.

What Hitchcock understood was that watching the movie was really a subset of the overall experience of going to a movie. There was more to the value proposition than what could be done on the piece of film itself. Getting the entire audience in place before the movie started not only kept the movie’s plot twists intact for everyone, it generated a more dramatic (and therefore more valuable) shared experience. The gimmick of the hyperbolic marketing tactics also primed audience expectations, creating a heightened sense of energy in the theaters before the movie even started.

In this example, Hitchcock is the brand. He was already successful by 1960 (Vertigo, Rear Window, North By Northwest), so audiences already wanted to see his next product. Like any product, Psycho needed to succeed on its own merits, strong brand behind it or not. And then the customer journey was re-engineered to make the entire experience more powerful.

From the customer perspective, these distinctions are all blurred: only Hitchcock could make Psycho, Psycho is emblematic of Hitchcock, and an exhilarating night in the theater is the third element, borne of both the brand and the product, while amplifying the power of both. That’s the essence of Experience Design.

Even the trailer for the movie is a 06:31 masterpiece of pacing and understatement. Click the image to take a look. If you haven't seen the movie yet, you'll pretty much have to after seeing this.

Of course movie-going and watching continued to change after 1960, and we can learn more by examining the changes Netflix has undergone over the past 15 years.

Netflix got its start with some astute observations of what was broken with the existing 1999 movie rental experience. A customer journey mapping exercise conducted then might have found that the major pain points were making the trips to and from the rental store, and the pressure to watch the film before the late fees kicked in. The insights that DVDs were easy to mail and that a subscription approach would eliminate late fees were the crucial game-changers.

That success created a new movie rental experience. Customers quickly grew to love the moment they saw their red Netflix envelopes in their mailboxes tucked in among the bills at the end of a tough day, and the anticipation generated by managing their queue of DVDs. That product experience became central to the Netflix brand itself.

Once video streaming proved viable, it completely bypassed that successful brand experience and its wonderfully tangible interactions. Netflix clearly recognized this at the time, so in late 2011 they split the streaming and DVD-by-mail services into two parts, launching the ill-fated Qwikster brand for the DVD rental service. Customers were both baffled and irate at the changes. Realizing the severity of the mistake, Netflix got rid of the Qwikster brand within four weeks.

It’s tempting to apply 20/20 hindsight to that failure, but it’s completely understandable why Netflix went with that approach. They believed they were looking at two fundamentally different value propositions, each with their own customer journey. But from the customer perspective, it was still about watching a movie with a minimum of hassle. To the customer, the delivery mechanism was just an option, not the actual value itself.

Netflix quickly righted the ship, and then delivered another category game-changer: the binge-watching phenomenon.

Everything from I Love Lucy to The Sopranos followed a model based on a weekly release of new content. Watching the show was the first element; talking about it with everyone else was the second. That wasn’t just fun, it was part of the business model itself. Creating 24 episodes per season also meant there were 24 weeks’ worth of commercial time, or premium cable channel subscriptions, that supports the whole enterprise.

Netflix flew in the face of this logic by dropping entire seasons of their own content, such as Orange is the New Black and House of Cards in a single moment. Sure enough, plenty of customers burn through those episodes in only a few days, knowing they would be waiting a year or more for a next season. Even so, Netflix subscriptions have grown steadily, refuting the inevitability of the one episode a week model.

All of these transitions have also changed the nature of what Netflix is, from being just a distributor to a distributor and a producer. A static brand strategy model would not accommodate such a radical change. Even physical products are finding themselves with the ability to transcend their category of birth very quickly these days.

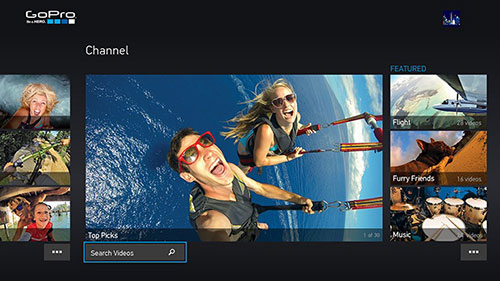

The rapid evolution of the GoPro camera is a great example of this. While it’s certainly a great piece of hardware, so much of what has made it successful would have been missed entirely with a standard approach to product, brand, and customer journey definition. But from an experience design perspective, it’s easier to envision.

On a traditional camera feature-by-feature basis, the GoPro made no sense. It had no viewfinder or display screen, so you can't compose the shot like every other camera ever sold to consumers. There's no auto-focus or zoom, and its very wide angle lens is really unflattering for a portrait.

But if you look at the camera within the experience it’s meant for, those standard camera buying and usage journey priorities don’t apply any more. You either wear it, or attach it to the reckless contraption you're riding. The camera isn’t being used just to document people who already do wild stunts, people are buying the camera so they can become a person who does wild stunts, and have the videos to prove it to everybody else. That kind of journey-alerting success opens up other value for GoPro to exploit.

The GoPro camera and the content it generates has been so compelling, GoPro launched its own media channel via the xBox platform, thus expanding the category in which it competes from technology hardware into entertainment. The hope is that advertising revenue will follow from other companies wanting to address the active, young audience GoPro already connects with. There's no good reason Nikon or Canon couldn't have done the same thing, other than their taking too limited a view of how consumers perceive the value cameras can deliver.

Experience Design is the mindset that makes the potential for these transformations apparent, without sacrificing the clarity and discipline that traditional Brand Strategy and Customer Journey Mapping have always provided. It accommodates the rapid change that is coursing through most product and service categories, since it is based on tracking and enhancing value as perceived by customers, not solely by the priorities of the producer. The definitions and paths to value are constantly in flux, so it is more effective to utilize an approach that tracks value above all else.

While I’ve focused on the entertainment category here, the lessons from these examples can work across many different categories. So, here are some guidelines that might help you see opportunities your competitors have missed:

1 Understand, define, and track Value, not just brand adjectives, product features, or existing category patterns. Consumer value perceptions are the result of an overall experience, not just your product or any other single factor.

2 Sometimes it’s the category patterns that need fixing more than the product. Consider focusing innovation efforts on re-thinking the customer journey, not just your product’s role within it.

3 Always consider the potential difference between your intent and the customer perceptions that intent creates. Remember the first time you heard a recording of your own voice? Sounded disturbingly odd, didn’t it? That’s what reality sounds like. The more you can adopt the perspective of someone outside your own experience, the more accurate your instincts will be.

4 The biggest competitive threat you face might not be your competitors. It’s missing a shift in how consumers perceive value, or even in assuming a new technology will create a shift, when it won’t.

5 Learn more about Experience Design. It really does provide a way to both recognize and integrate approaches to Brand Strategy and Customer Journey Mapping to create a more powerful outcome for you and your customers.

And have a few Reese’s cups while you’re at it. Call it a necessary research expense.