Everyone in Bedford Falls knows how good a person George Bailey is, and how much he has sacrificed for the sake of the town and his family. Even his nemesis, the miserly, powerful, and predatory Mr. Potter knows George is worth far more than he earns.

But does George understand that truth about himself? Of course he does, but he never acknowledges it, perhaps specifically to avoid the pain and humiliation of confronting that fundamental truth.

That’s why Potter, the villain in the classic Holiday movie It’s a Wonderful Life, is more than willing to explain George’s own life to him, in excruciatingly accurate detail.

If you’re familiar with the movie, you know which scene I’m talking about. If you haven’t seen it (seriously?), here it is:

Potter’s motives are sinister, but he throws George and the audience a major curve: he tells the honest truth. Potter didn’t lie, deceive, or condescend one iota. Nor was he trying to seduce him with false praise; it was a spot-on character assessment and performance review of someone who’s never worked for him.

George’s reaction to this affirmation of his own value, and an offer of a huge career lift and pay increase, is one of elation, then confusion followed by frustration and rage. The protective shield he’s used to hide his own despair has been pierced, not through deception or betrayal but by something far more powerful: Empathy.

“Empathy [is] what a marketing exec needs to persuade a target audience, and what a designer needs to align her own intent with that of an end user.”

Empathy (not to be confused with the kindness of sympathy) is the ability to adopt the perspective of someone other than yourself. It’s essential for sizing up and developing a strategy to defeat any manner of opponent, but it’s also what a marketing exec needs to persuade a target audience, and what a designer needs to align her own intent with that of an end user.

Like any form of power, Empathy is morally neutral. It can be wielded for either encouragement or as a weapon. George was angry at Potter’s display of empathy not because he was wrong, but because everything Potter said was true. Truth is the core of empathy, and that’s why it’s often so difficult for the hero, and ourselves, to fully embrace. That’s the vulnerability a crafty villain exploits.

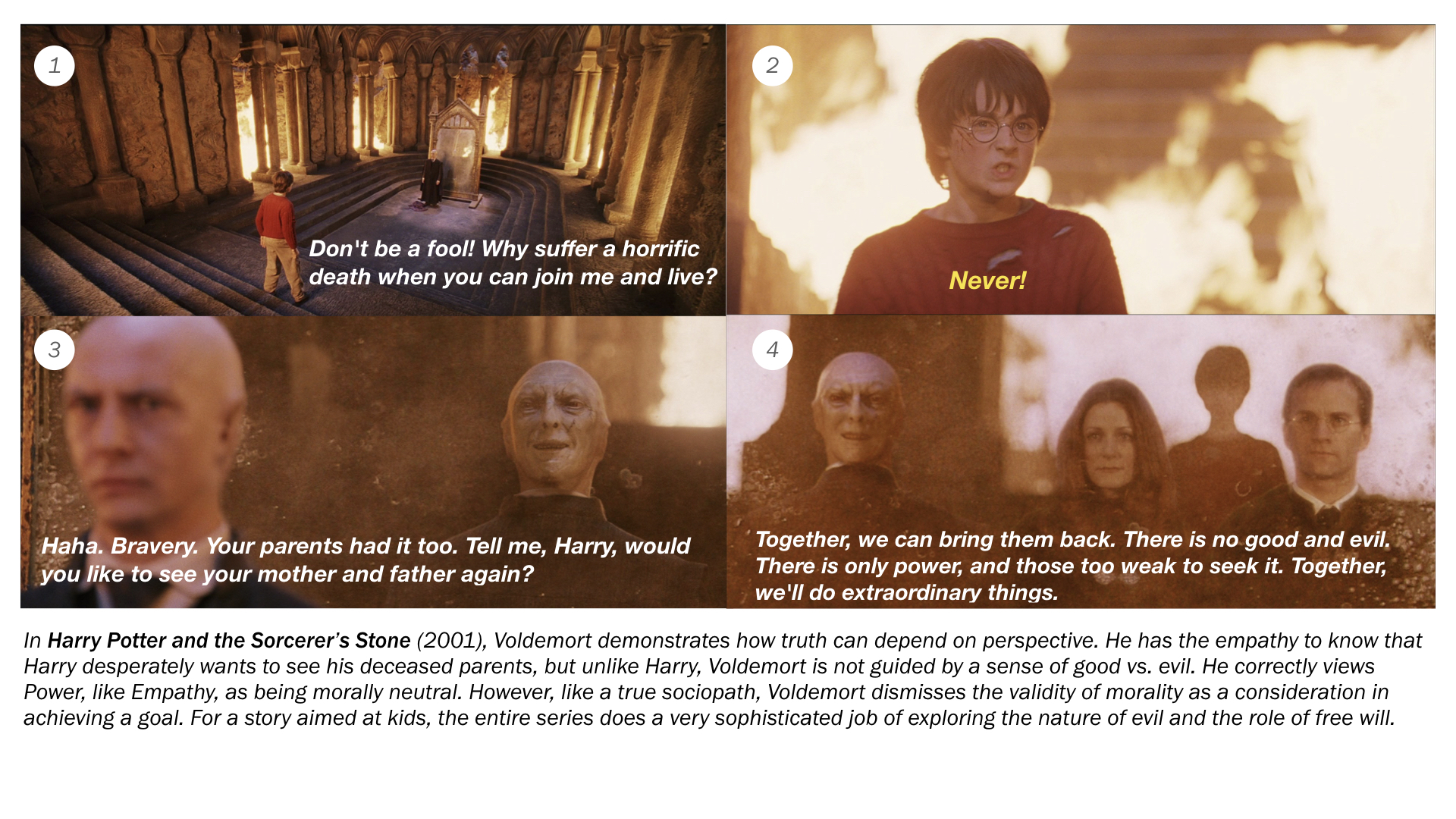

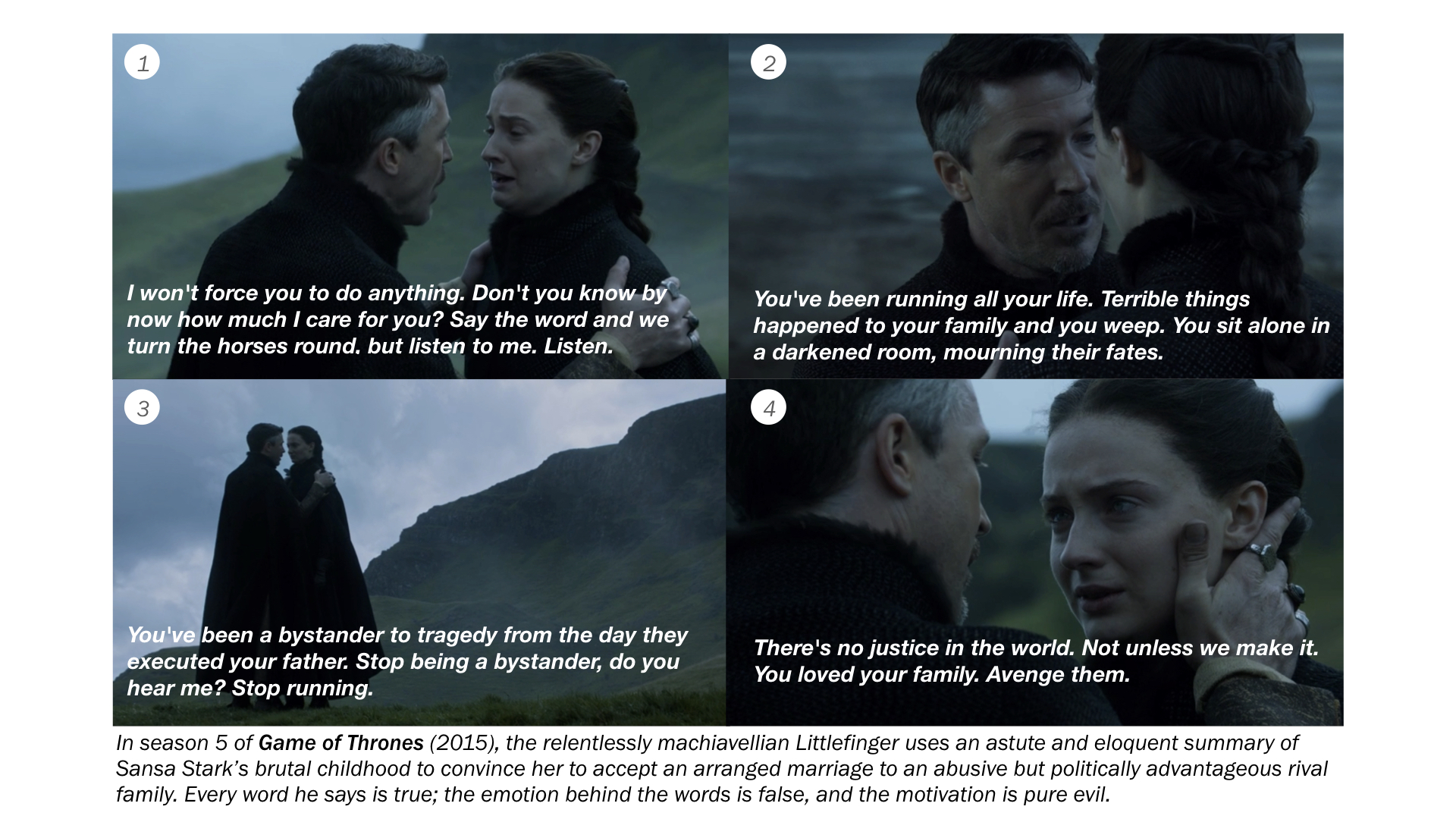

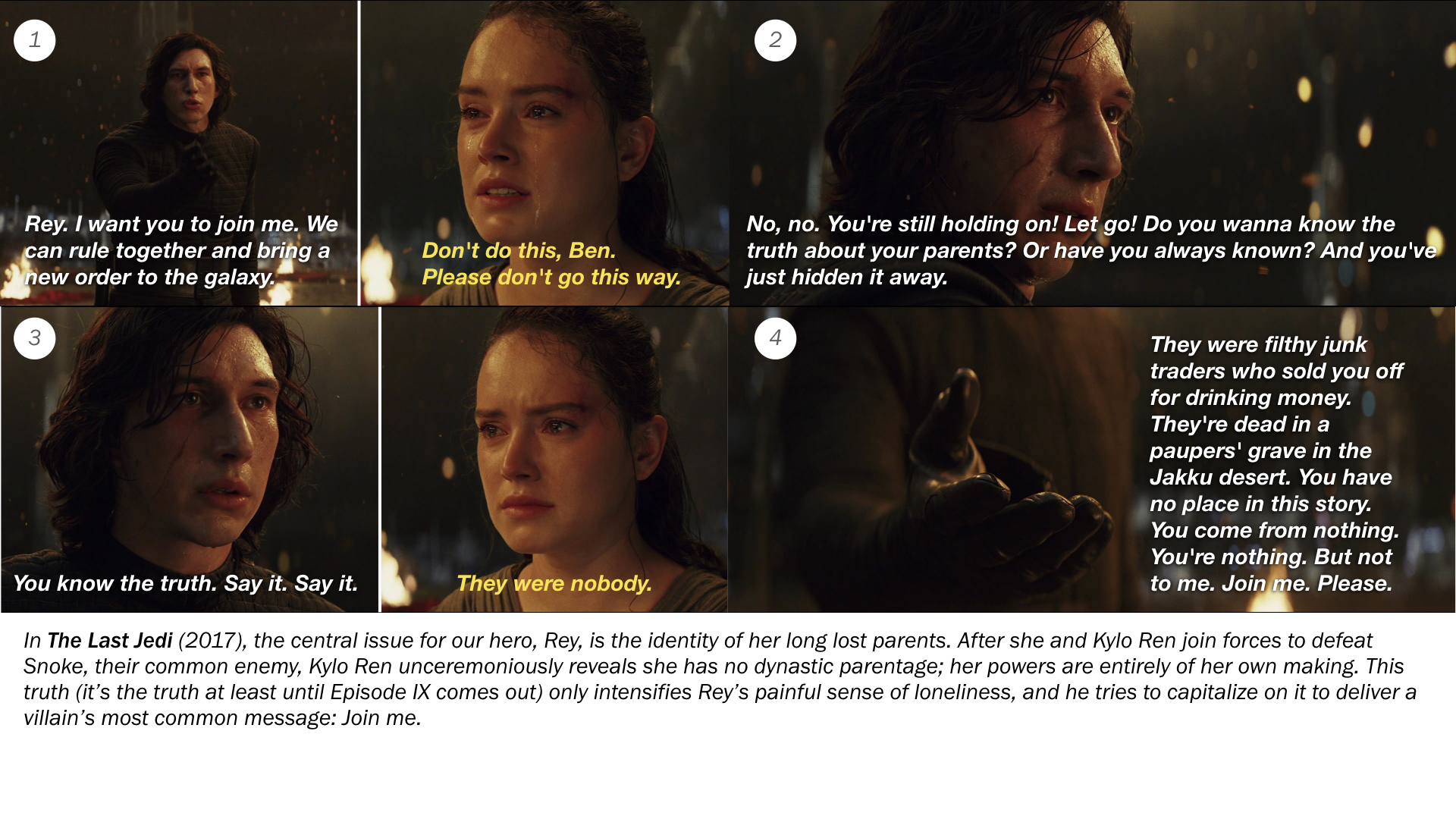

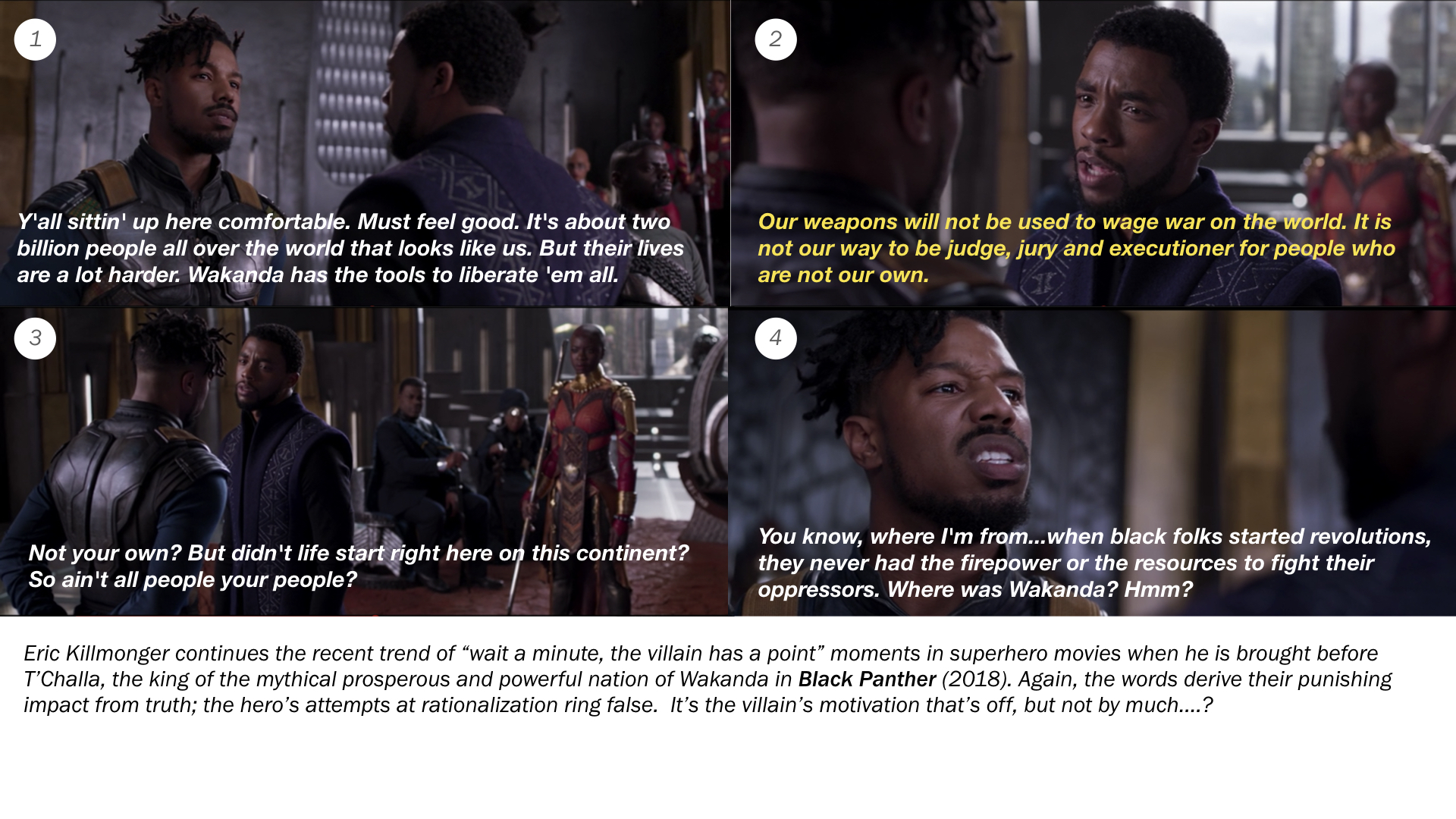

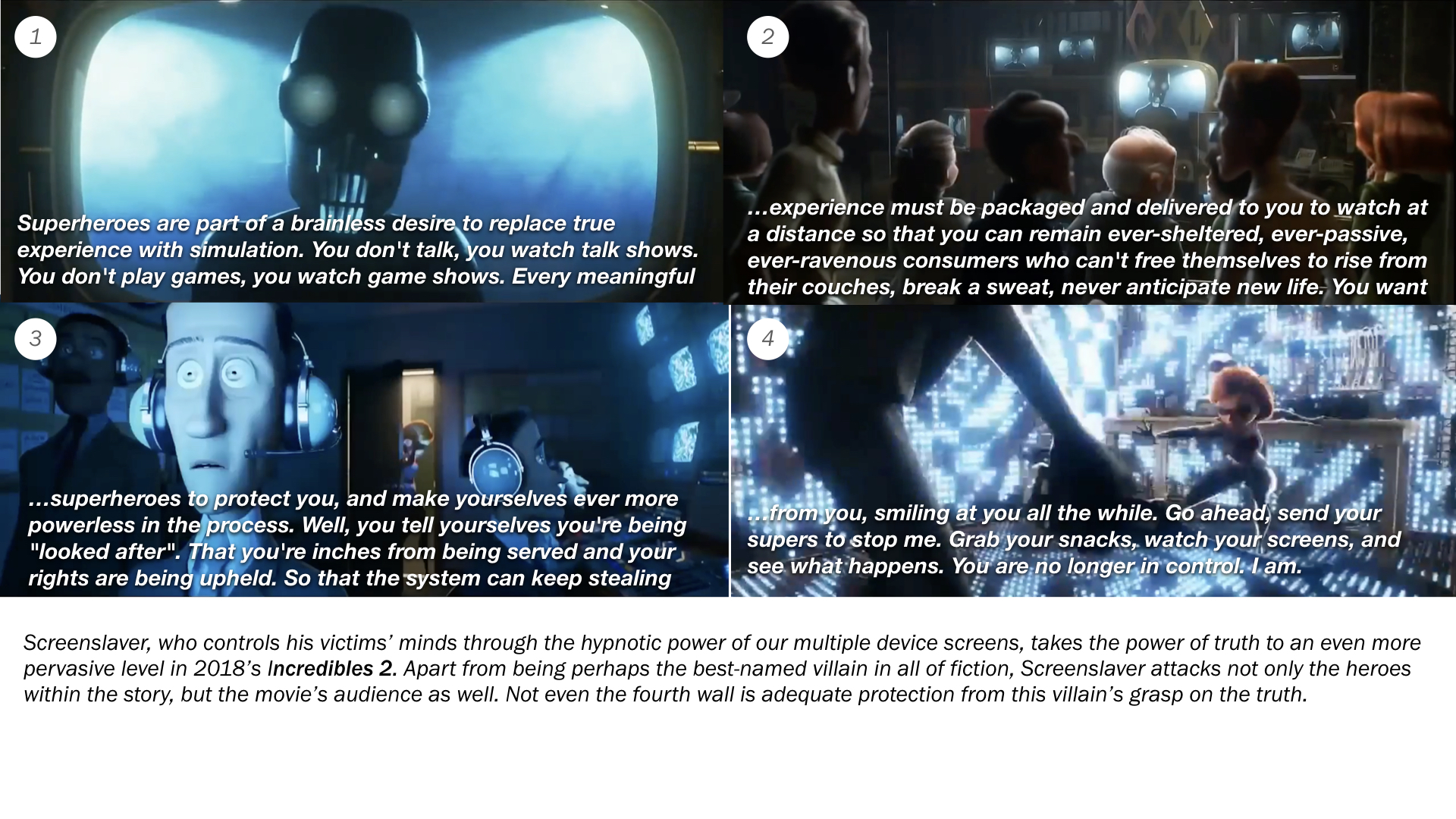

As a consultant and researcher, I aspire to the achieve the unsettling level of empathy Potter displayed. There’s also plenty to learn from more recently conceived bad guys like Voldemort, Kylo Ren, Littlefinger, Killmonger, and Screenslaver, all of whom were created to be complex and insightful enough to startle their various protagonists into a least a moment of uneasy self-reflection.

Of course, I want to use my powers for good, but to do so, I often need to quietly adopt the persona of a villain in order to get a client to understand and confront the truths they have become so adept at denying. And just like George Bailey (and respectively, Harry Potter, Rey, Sansa Stark, T’Challa, and Elastigirl), these clients are often taken aback at needing to confront what they already know about themselves, their companies, and what they consider their missions to be.

There’s just something fundamentally unsettling about confronting the external echo of an internal truth, regardless of how flattering it might be. It’s like listening to a recording of your own voice. It’s obviously you, and everyone else agrees that’s exactly what you sound like, but…yuck.

It’s the ability of a skilled external observer to see what the heroes are unable to articulate about themselves that’s so disarming. Outsiders aren’t supposed to figure those things out, but most of the time it’s being an outsider that enables the necessary clarity to pull it off. It’s my job to do that with a villain’s skill, but with an ally’s heart.

“It’s like listening to a recording of your own voice. It’s obviously you, and everyone else agrees that’s exactly what you sound like, but…yuck. ”

Well, what counts as truth? In a previous video post, I went to some lengths to explain the differences between Data, Information, and Knowledge. All of these are pursued in the hopes of defining some sort of truth, and then figuring out what to do about it. The catch is that as you move up to more valuable things like Knowledge and Understanding, more subjectivity enters the picture.

That means truth depends in some way upon the observer (please hold the quantum physics comments for now), and that opens to door to denial. If there’s more than one way to define a truth, and the original truth is any way uncomfortable, chances are it will be actively avoided.

The way to avoid avoiding the truth is to realize that just because the same knowledge can describe more than one truth, it doesn’t mean there are infinite truths involved. It’s more like defining the “true” shape of a mountain. Just because a mountain appears to have different shapes depending on your vantage point, the mountain’s true shape doesn’t change. The other truth is that the true shape of the mountain is much clearer to the person who views it from afar, not the person whose face is pressed against it while trying to climb it.

You may not have something as dramatic (or convenient) as a conniving, sinister villain out to destroy your organization, but you can create a valuable proxy for one by combining the perspectives of those entities who do constantly push against your own noble quest:

You have customers and prospects who either are ignorant of the full range of what you provide, or fail to see the value in paying what you’re asking for it.

You have competitors who constantly evaluate your product line to look for weaknesses, or to copy your best ideas and sell them for less.

You have direct and indirect competitors trying to poach your best employees to join their ranks, and prevent the best young talent from considering working for you.

You have press and analyst teams treating your announcements and decisions with skepticism, and investors who are never, ever satisfied with quarterly results.

And then there are your own people, who might be resisting a change that’s desperately needed to remain competitive, because their departments or careers would be damaged by acting in the best overall interest of the company.

If you could create a single meta-villain by aggregating all of those points of view about your company, there’s a good chance that assessment would be very accurate, and surprisingly positive. Just like old man Potter, these entities wouldn’t be so concerned about you if you were truly useless.

The weird thing is, it might also confirm what you already know about yourself and your organization. The key is to confront those truths on your own terms, not theirs. That’s never easy, but that’s the job. If you were to get a positive but brutally honest assessment of your situation, who would say it, and what would they say?

George Bailey had to be driven to the brink of suicide and be confronted via divine intervention before he could realize everything Potter told him was indeed true, but couldn’t believe about himself. Don’t let it get to that point in your company; Clarence Odbody isn’t here to bail you out.